The Overprotected Kid, is a long, very interesting, article from The Atlantic about how kids used to grow up not that long ago.

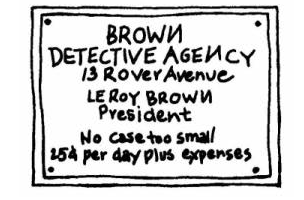

All you need to do to see the stark difference in kids today versus kids just a few decades ago is read some literature about kids from that time. I’ve been reading Encyclopedia Brown stories with my son, and there are all kinds of descriptions of Encyclopedia traveling all over town on his bike or on the bus, all by himself. He interacts with other adults. He spends a lot of time doing things without any adults at all around. These are not described as atypical behavior, it’s just a matter of fact. Encyclopedia is 10 years old.

Here are some choice excerpts from the Atlantic article:

A playground that sounds awesome:

If a 10-year-old lit a fire at an American playground, someone would call the police and the kid would be taken for counseling. At the Land, spontaneous fires are a frequent occurrence. The park is staffed by professionally trained “playworkers,” who keep a close eye on the kids but don’t intervene all that much.

The difference in supervision between then and now:

My mother didn’t work all that much when I was younger, but she didn’t spend vast amounts of time with me, either. She didn’t arrange my playdates or drive me to swimming lessons or introduce me to cool music she liked. On weekdays after school she just expected me to show up for dinner; on weekends I barely saw her at all. I, on the other hand, might easily spend every waking Saturday hour with one if not all three of my children, taking one to a soccer game, the second to a theater program, the third to a friend’s house, or just hanging out with them at home. When my daughter was about 10, my husband suddenly realized that in her whole life, she had probably not spent more than 10 minutes unsupervised by an adult. Not 10 minutes in 10 years.

Are playground’s safer?:

We might accept a few more phobias in our children in exchange for fewer injuries. But the final irony is that our close attention to safety has not in fact made a tremendous difference in the number of accidents children have. According to the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which monitors hospital visits, the frequency of emergency-room visits related to playground equipment, including home equipment, in 1980 was 156,000, or one visit per 1,452 Americans. In 2012, it was 271,475, or one per 1,156 Americans. The number of deaths hasn’t changed much either. From 2001 through 2008, the Consumer Product Safety Commission reported 100 deaths associated with playground equipment—an average of 13 a year, or 10 fewer than were reported in 1980. Head injuries, runaway motorcycles, a fatal fall onto a rock—most of the horrors Sweeney and Frost described all those years ago turn out to be freakishly rare, unexpected tragedies that no amount of safety-proofing can prevent.

Is the world more dangerous now?:

But abduction cases like Etan Patz’s were incredibly uncommon a generation ago, and remain so today. David Finkelhor is the director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center and the most reliable authority on sexual-abuse and abduction statistics for children. In his research, Finkelhor singles out a category of crime called the “stereotypical abduction,” by which he means the kind of abduction that’s likely to make the news, during which the victim disappears overnight, or is taken more than 50 miles away, or is killed. Finkelhor says these cases remain exceedingly rare and do not appear to have increased since at least the mid‑’80s, and he guesses the ’70s, although he was not keeping track then. Overall, crimes against children have been declining, in keeping with the general crime drop since the ’90s. A child from a happy, intact family who walks to the bus stop and never comes home is still a singular tragedy, not a national epidemic.